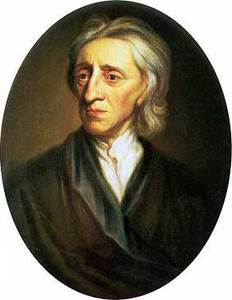

John Locke (1632-1704)

Born in Somerset, England, John Locke was a noted philosopher—the first of the British empiricists— political adviser, and physician. As a student at the Westminster School, Locke endured the typical mid-seventeenth-century educational regimen reserved for adolescent boys: strict adherence to rules, severe punishments, and rote memorization of both the principles of grammar and large selections of Latin and Greek verse. Undoubtedly, Locke's dissatisfaction with his education at Westminster was responsible, to a significant extent, for both his stalwart support of home schooling—the preferred method at the time for educating girls—and private tutors, as well as his forceful criticism of institutional education.

But much of Locke's view on education and the proper development of children—set forth in a series of letters to a cousin and later published as Some Thoughts on Education—also reflected his philosophical writings on the nature of knowledge and human understanding (though scholars differ on the precise relationship between these two bodies of work). In An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Locke argued that the human mind at birth is a tabula rasa (blank slate), entirely devoid of any ideas or other mental content. All the content of the active human mind is derived from the data of sense experience, which is then transformed into increasingly complex ideas through reflection and reason. Crucial to Locke's philosophical view, and of great significance for his thoughts on education, was his emphasis on the role of experience in the acquisition of knowledge. Indeed, in the first paragraphs of Some Thoughts on Education, Locke contended that the depth and breadth of one's knowledge, both moral and practical, is overwhelmingly a product of education and experience, as opposed to natural intellect. Locke did recognize that children are born with differing aptitudes and inclinations, and he believed that, for the most part, these natural elements could not be significantly altered. It is for this reason, Locke argued, that curricula must be designed that fit the parameters of a child's natural genius. But without experience these aptitudes cannot be detected nor, of course, developed. And children are best able to develop their

John Locke (1632-1704) was a proponent of home schooling and private tutoring rather than the strict regimen that most adolescent boys were required to follow.

The interest in Locke's writings on education for his successors is clear: By the end of the nineteenth century Some Thoughts on Education had been through literally dozens of English editions, as well as several editions in French, German, and Italian.

Bibliography

Cleverly, John, and D. C. Phillips. Visions of Childhood: Influential

Models from Locke to Spock. New York: Teachers College Press, 1986.

Simons, M. "Why Can't a Man Be More Like a Woman? (A Note on John Locke's Educational Thought)." Educational Theory 40 (1990):135-145.

Publications by Locke

The Works of John Locke: Some Thoughts on Education. London: Printed for Thomas Tegg, 1823.

Locke, John. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, edited byPeter H. Nidditch. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1975.

Richard M. Buck

Additional topics

- Mainstreaming

- Learning Disabilities - Definition Of Learning Disabilities, The Discrepancy Issue, Learning Disability Subtypes, Causes And Diagnosis, Outcomes - Conclusions

- Other Free Encyclopedias